An Unsung Architect of Micro-Computing

Recently, I was asked to join a conversation about computing’s beginning. Some of the questions floated were: “When did standard computing really begin?” “What caused it?” “How does it affect us today, if at all?” These individuals had backgrounds in programming on Mac, Windows, and Linux systems, yet proved to be strangers to the history that laid the foundation beneath their code, so I decided to narrow down my answers to microcomputers.

While this is a “blast from the past”-type article, it is different in that this one can be considered historical and/or personal opinion. The late 1970s through the 1980s were a transformative time when many of the conventions, standards, and practices that we take for granted today were being established.

CP/M

If there was any one thing that began the shaping of micro-computing, it would have to be the CP/M operating system. It played a central part in the development of personal computing, both in software and hardware realms. The era of CP/M, in my opinion, represents the beginnings of microcomputer history. It was a time of rapid innovation, community building, and exploration as enthusiasts, developers, and entrepreneurs were beginning to shape what would become our current, modern digital world.

CP/M was the first operating system I ever used. I happened to be working at a small college and several Kaypro II computers were purchased and it was here that I was introduced to computing and CP/M. Designed for the Intel 8080 8-bit processor and a modest 64 kilobytes of memory, CP/M stood for Control Program for Microcomputers. It was an era where computing power that we now take for granted was a marvel, a luxury. CP/M was later adapted for other 8-bit processors like the Zilog Z80 and evolved into multi-user variants for 16-bit processors.

CP/M was developed by Dr. Gary A. Kildall, while working for Intel Corporation, in 1974. In 1975, he and Dorothy Kildall founded Digital Research, Inc. (DRI), making CP/M the most popular operating system for microcomputers by 1977. The combination of CP/M and S-100 bus, the first expansion bus that became an early standard in the microcomputer industry, ensured CP/M’s dominance in businesses from the late 1970s into the mid-1980s.

Hardware

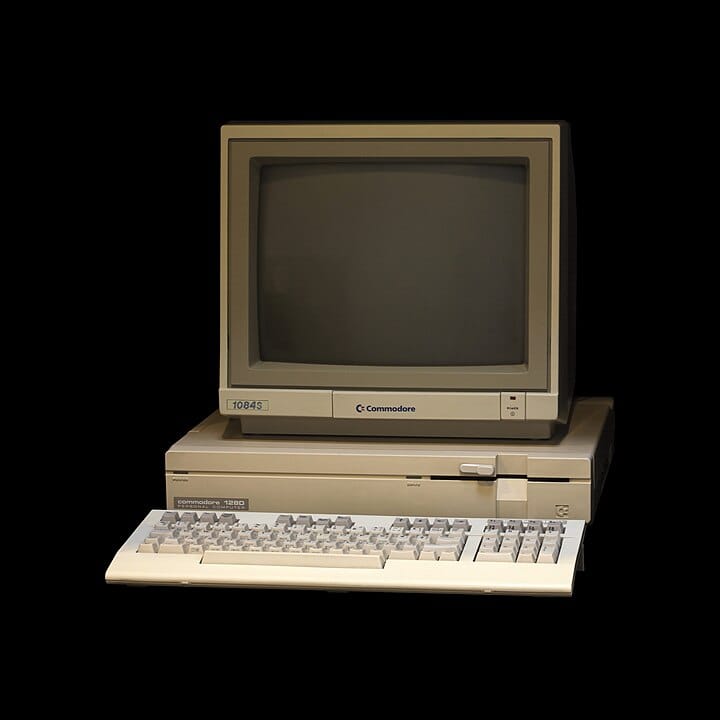

CP/M’s adaptability was legendary; it seemed to run on anything. My experiences stretched across a spectrum of machines, from the versatile Commodore 128, which juggled its native system, a Commodore 64 mode, and a CP/M mode, to the Osborne 1, Zenith Z-89, and the TRS-80 Model II. And while I never tried the CP/M cartridge for the Commodore 64, the existence of such an adapter says much of CP/M’s ubiquity.

Introduction of BIOS

This universal adaptability comes from CP/M’s ingenious architecture, which separated the machine-dependent BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) from machine-independent components. This separation allowed CP/M to run across a wide array of machines with minimal modifications. It was Gary Kildall who coined the term “BIOS” to describe this pivotal part of the operating system that interfaced with the hardware, an invention that became a critical development in the evolution of personal computers.

Before CP/M, the personal computing landscape was incredibly fragmented. Each manufacturer typically created its own hardware and software, leading to a situation where programs and applications were not transferable between systems. This required software developers to rewrite or adapt their applications for each different machine, which was time-consuming and inefficient.

As more businesses and individuals began adopting computers, the need for standardization and compatibility became clear. There was a growing demand for a common platform that would allow software to be more portable and hardware to be more interoperable. CP/M emerged as a response to this fragmentation.

Cruising on the S-100 Bus

The introduction of the S-100 bus further wired the future of computing, offering a spine of expansion capabilities. As the S-100 bus became more widespread, it helped standardize the hardware side of personal computing. Manufacturers began producing a wide range of compatible peripherals and expansion cards, making it easier for users to upgrade and expand their systems.

The popularity of the S-100 bus complemented the rise of CP/M. Since CP/M could run on any hardware that provided a certain level of compatibility, the S-100 bus’s standardization helped solidify CP/M’s position as a versatile and popular operating system. Essentially, the S-100 bus handled the hardware standardization, while CP/M tackled the software side.

The move for hardware standardization was no accident. CP/M’s requirement for a standard set of interfaces (especially for disk access and I/O operations) nudged hardware manufacturers towards adopting common standards. This was critical in an industry that was rapidly evolving and had no established norms. Today, CP/M is no longer a competitor as an operating system, nor is hardware, such as the S-100 bus, used today. However, the design philosophies and requirements of CP/M influenced subsequent hardware design, including the IBM PC. Manufacturers recognized the value of creating hardware that could support popular operating systems out of the box.

Software

CP/M solved the problem of the absence of a common operating system. Unlike today, where a few operating systems dominate the personal computer market, the early days saw no such standardization. Each system might have its unique operating system, if any, and users often had to understand the intricacies of their particular machine to use or program it effectively.

Standardization of software development

CP/M also played a vital role in the standardization of software development. By providing a common platform across various hardware, CP/M enabled software developers to write programs that could run on any CP/M-compatible machine – significantly reducing the development effort and barriers to entry for software creators.

CP/M’s popularity also led to a vibrant ecosystem of software development, ranging from business applications and programming tools to games. This support for a wide range of applications, including word processors like WordStar, spreadsheets like SuperCalc, and programming languages like BASIC and Pascal, set the foundation in making personal computing useful for both business and personal users and in demonstrating the commercial viability of software as a product.

The CP/M era was marked by a strong community ethos, with user groups, newsletters, and software sharing being commonplace. Learning about, and how to use these systems, in those early days, wasn’t always easy and often a challenge (a common thread among many early computing enthusiasts). The learning curve was steep, especially with terse documentation and less interactive debugging tools. The effort spent in learning led to a deep and intuitive understanding of computing principles, and a certain resilience and problem-solving mindset that was invaluable. The community shared their knowledge and accelerated software development and adoption.

Software installers

Another invention of note was the software installer. The concept of software installation, including installers, became more pronounced with CP/M. The need to distribute software that could work on different configurations without requiring extensive manual setup was a driver behind this innovation. This seems commonplace today, but this move towards standardized installation processes was a precursor to the software installation routines we see today. It represented an early understanding of the need for user-friendly software deployment in a diverse hardware environment.

Conclusion

CP/M is considered obsolete today – a single-user operating system that ran on what we see as limited hardware today. CP/M’s adaptability, however, started a rich software ecosystem and prodded the industry towards hardware standardization. The operating system’s design principles, particularly its separation of machine-dependent and machine-independent components, and its impact on software distribution and installation processes, were instrumental in shaping the micro-computing as we know it today.

CP/M arrived just when technology, business, and human creativity crossed paths and it had a hand in affecting all of it, leading to rapid evolution and sometimes unexpected turns. CP/M’s place in this history contributes to our understanding of modern computing and provides insight into where technology might go next. Looking back at CP/M, I don’t just see an operating system; I was witness to its chapter in the grand narrative of computing and its story is a testament to the enduring power of adaptability, vision, and community in shaping technology. From the beginnings of CP/M sprung an industry and a world that continues to evolve, echoing the legacy of those early days in every click, every code, and every computer.